An English contract manager asked me the other day about the use of ‘can’ and ‘may’ in modernised contracts. He and his US colleagues thought that ‘may’ seemed to be dominant in the terms they’d been debating, although it was not used consistently even within one set of terms.

I agree that ‘may’ is used more than ‘can’ in contracts. I think the choice matters less than consistency. Both are well understood and they mean almost the same, so the choice is unlikely to cause a misunderstanding.

What is the difference?

There is a subtle difference between ‘can’ and ‘may’ in modern English. Some say it’s a difference of meaning but the Oxford English Dictionary says it’s a difference of tone.

In speech and informal writing, we normally use ‘can’ to ask or give permission. ‘Can I have another bit of cake, please, Mum?’ ‘No, you can’t’.

According to the sticklers, this common usage is incorrect. ‘Can’ indicates ability, not permission. If the child is able to lift the cake from the plate to her mouth and isn’t yet full, she has the ability to eat the cake.

If the mother is a stickler, the child might ask “May I have another piece of cake, please, Mother?” If the child gets it wrong, Mother might say “I expect you can, but no, you may not”. But, even if she put her request the ‘wrong’ way, child and parent both know the real question is whether the child has permission. It’s not clear if Mother is teaching the child better English or better manners.

Which do contract users normally use?

As with other writing, the more a contract speaks as its users do, the easier the users find it to read and follow.

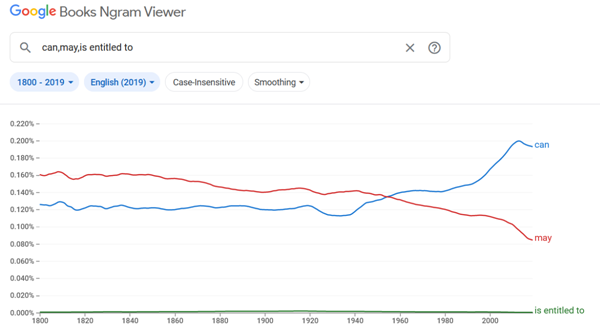

In general writing, ‘may’ is increasingly old-fashioned. A comparison using Google Ngrams shows that, in books on any subject printed from 1800 to 2019, the use of ‘may’ has declined slowly and was overtaken by ‘can’ in about 1954, 30 years before ‘must’ overtook ‘shall’.

Which do we normally use in contracts?

In traditional contracts, the home of formal and old-fashioned language, ‘may’ is still dominant. For example, in the 524 pages of the UK government’s Model services contract, v1.09 (2010), the may:can ratio is 355:54. (In the same contract, the shall:must ratio is 1589:111.)

Even in contracts drafted in a less traditional style, I find, like my correspondent, that ‘may’ outnumbers ‘can’. But that doesn’t tell you which is better.

In my own contracts, I still use ‘must’ and ‘may’. My commitment to write in the users’ language tells me to prefer ‘can’, but I fear resistance from the lawyers who already reject ‘must’. I don’t want to fuel their resistance by suggesting a word that is, even arguably, incorrect. Maybe it’s time for me to gather up my courage and change that too.

May not: ambiguous

When you deny permission, think twice about ‘may not’. In ordinary speech, ‘Cinderella may not go to the ball’ could mean two things:

- Cinderella is not allowed to go to the ball. In a contract, she has a duty to stay away; she must not go there.

- Cinderella is not committed to going to the ball; maybe she will go, maybe not. In a contract, she has permission to attend but no duty to do so.

For example, in the model services contract, we see:

- Prohibition. The Guarantor may not assign or transfer any of its rights and/or obligations under this Deed without the prior written consent of the Authority. Schedule 10, Clause 8.2.

- Possibility. The Sub-licensee acknowledges and agrees that damages alone may not be an adequate remedy for any breach by the Sub-licensee of any of the provisions of this Agreement. Annex 2, clause 1.4.

- Room for argument? Except where an audit is imposed on the Authority by a regulatory body or where the Authority has reasonable grounds for believing that the Supplier has not complied with its obligations under this Agreement, the Authority may not conduct an audit of the Supplier or of the same Key Sub-contractor more than twice in any Contract Year. Schedule 7.5, clause 1.2.

If the contract really means to prohibit the Authority from auditing the supplier more than twice a year, as I think it does, then saying the Authority ‘must not’ do so would remove the room for argument. Or, for consistency with the rest of this contract, ‘shall not’.

A similar ambiguity could affect ‘may’: does it express permission or a possibility? In the context of a contract, I haven’t yet seen this cause a problem in practice. I’d like to hear from anyone who has.

Cannot and must not

‘Cannot’ does not suggest doubt. If Cinderella signs a contract saying she cannot go to the ball, then it’s pretty clear she must not go.

But beware if the contract also says Cinderella ‘must not’ do other things. This inconsistency opens up an argument on interpretation: ‘there must be a difference, otherwise the careful drafter would have used the same word in both places’.

Peter Butt gives an example in The Lawyer’s Style Guide. Interpreting a statute, an Australian court held that ‘cannot’ denied capacity, making the prohibited action invalid, but ‘must not’ had some other effect. In some clauses of the statute, ‘must not’ imposed criminal or other liability for doing the prohibited act. In others, not discussed further in the judgment, ‘must not’ imposed no such liability and its effect remains unclear (to me, at least). The key provision in the dispute was a ‘must not’, so an action taken in breach of the prohibition was valid. But there were other reasons behind this decision, including the court’s understanding of the purpose of the legislation and the justice of the case: 2 Elizabeth Bay Road Pty Ltd v Owners Strata Plan No 73943 [2014] NSWCA 409, paragraphs 34 to 48.

Is entitled to: unstated duty or permission?

The following formula looks as if it’s creating a right: “X is entitled to…” (or, confusingly, X shall be entitled to …).

Usually, this formula disguises a duty or permission. For example, if X is entitled to end the contract, that’s permission and “may” does the same job. Or maybe X is entitled to exercise an option to buy property. In that case, somebody owes X a duty to transfer the property, if X exercises the option. Let’s hope that the contract spells out who that is and what they have to do.

These formulas are wordy, old-fashioned, and legalistic. Another reason to avoid them is the risk that, by focusing on the receiving end of the performance, the drafter may miss out important information about who must perform what. At worst, the unidentified person in a position to deliver the promised performance might not be party to the contract, so not bound to do what it says.

So, it’s a good drafting habit to stick to ‘must’ for a duty and ‘may’ or ‘can’ for permission.

The value of consistency

While there is goodwill and the parties are cooperating to perform the contract, these shades of meaning are unlikely to cause a misunderstanding.

In the rare case of a dispute that doesn’t yield to a commercial settlement, the lawyers try to support their desired result by analysing a tiny fragment of the whole contract in more detail than the drafters ever did. An inconsistency between that fragment and the rest can produce arguments like the one used in the Australian case. It isn’t the strongest argument, since contracts do contain redundant and inconsistent language. But a lawyer may use it and a judge may accept it, as a makeweight to buttress other reasons, especially in a contract that really does look carefully drafted.

Consistency alone won’t prevent a dispute, or stop the lawyers analysing the contract in detail, or help you predict which bit of the contract they will focus on. But consistency still helps express clearly who must do what, which makes it good drafting practice. Use the same word to mean the same thing, throughout the contract.

Action

- Comment on this post to share your experience of drafting with ‘can’ and ‘may’.

- Read the post on Must, shall and will in business contracts.

- Read the book Clarity for Lawyers for more ways to achieve user-friendly contract drafting.

- Follow the blog.